Economic rules hurt most Americans

The Upriver Current

An interview with Dr. Ryan Mattson and Ben Johnson

Many politicians say that “if you work hard and play by the rules,” then even low-income citizens can move up the economic ladder. But what if the rules are designed to only benefit the wealthiest Americans? In other words, what if the economy is rigged to work against average people? That’s the central thesis of our new book Inequality by Design: How a Rigged Economy Fractures America and What We Can Do About It.

In their book, economist Ryan Mattson and coauthor Ben Johnson argue that more than four decades of policy changes have condemned all people, except in top income brackets, to repetitive cycles of downward mobility. The growing economic inequality corrodes communities, jobs, schools, and civic cohesion. You can learn more about this important book here.

In this issue of The Upriver Current, I share a shortened version of my recent interview with Ben and Ryan. Ben is a writer whose academic work has focused on international relations and public policy. While working as a first responder in Delaware, he served some of America's poorest people, seeing firsthand the impact of inequality in America. Dr. Mattson is a macroeconomist with a PhD from the University of Kansas. Much of his research is focused on the impact of economic policies on ordinary Americans.

Glenn: Let’s start with an overview of what inequality is? Could you provide us with a 30,000-foot view of what's happening in the United States?

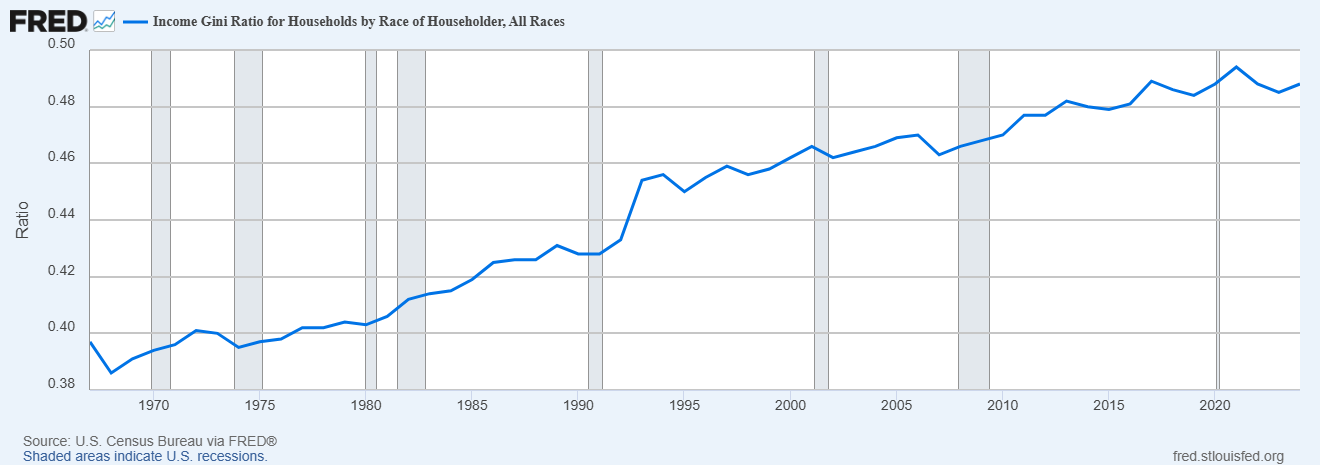

Ryan: The best way to measure inequality is with something called the Gini Index. This shows trends back to about 1967. It's an elegant and nice mathematical measure. It shows us is that inequality in the US has been increasing over time. The graph below is from the Federal Reserve. As the line goes up, it indicates increasing inequality.

What we see is that inequality was dropping after World War II. Then, in the 1980s, we see everything change. Thus, older generations had a different economic situation than we have today. Younger generations have been living in a context of increasing inequality.

Glenn: Ben, perhaps you could give us a perspective based on your work as a first responder in Delaware. You know, we can look at these graphs and things, but there's an on-the-ground reality.

Ben: So, I worked as an EMT in Wilmington. For those who don't know, Wilmington is the backup financial hub for New York City and the home to some of the largest credit card companies in America. There are many shiny, financial buildings in the middle of it, but it is surrounded by nineteenth century row houses and abandoned factories. And so, as a as an EMT, I would be out literally in the street, you know, putting a bandage on someone who had been shot, or dealing with someone who had an untreated medical condition because they couldn’t afford to go to a doctor. And literally three blocks away are tall corporate buildings where people are funneling hundreds of billions of dollars around the country. That was a visual image of the inequality in America.

Glenn: For a lot of people inequality feels kind of normal for them, especially for younger generations. They have grown up with the experience of it. But what was normal for previous generations is not the norm today. Right?

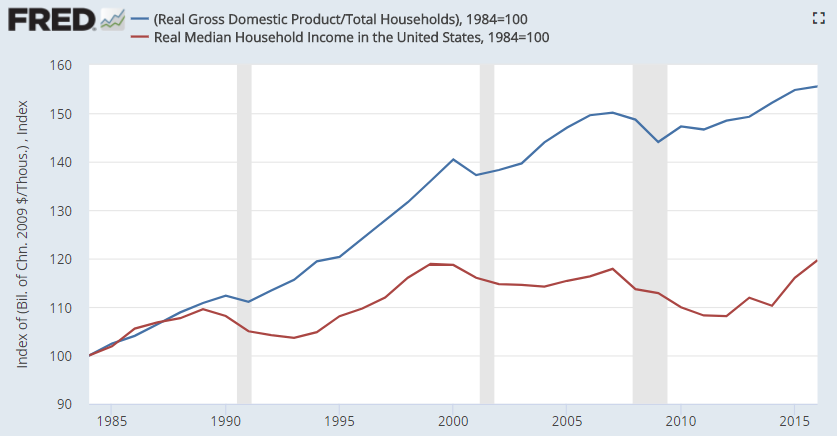

Ryan: That’s right. We have this increase in inequality that you see throughout the 80s and 90s. The next graph shows the increase in the gap between the wealthy and everyone else in America over time.

The top line shows an ongoing rise in GDP. The lower line shows real median household income. You see through the 40s, 50s, and 60s that the inequality gap was a small stream. There was a small difference between worker productivity, what they're what they're able to produce, and what they're getting paid. But then you see in the 80s that that stream turns into a flood. We see workers’ productivity increase quite a bit, but we see our pay stagnate.

Glenn: So, what you’re saying is that during the post-war generation, people saw a massive economic boom and most people shared that wealth. Then, starting in about 1980, policy designs changed and Americans shared less and less of the rising US wealth. Is that right?

Ryan: Yes. Starting in roughly the 1980s, you see that the wages stagnate even as GDP goes up.

Glenn: One of the things that shocked me in the book when I was editing it was the RAND Corporation study you cited. Perhaps one of you guys can share about that study. It's shocking.

Ben: Sure. The RAND Corporation is not exactly like, how do I say this, a bunch of wild-eyed Marxists. Far from it. But they estimated that over the course of this study, between about 1978 and 2018, more than $50 trillion in wealth had been transferred from the bottom 98 percent of people to the top two percent.

Ryan: That’s probably an understatement. If more Americans had shared that wealth in terms of wages, they would have spent or saved the money. If they had saved it, they would have earned interest on that capital. Without that wealth, many people lost that opportunity for capital gains and, moreover, saw declining credit scores, which means they often paid higher rates on loans.

Glenn: So, let's shift gears and talk a little bit about some of the policy designs that caused this type of problem. These are policy choices that have been made over roughly fifty years that have gradually, incrementally, caused the widening gap between average Americans and the wealthiest Americans. You argue that politicians have designed policies that strongly benefited the upper 10 percent of Americans. I realize this is a big, complicated topic, but perhaps share an overview.

Ryan: For example, if you have a lot of money and you put that money into capital gains, you’re not earning a salary for working. You've just got a big account that makes money. That’s fine, but the tax policy says that you are taxed at a much lower rate on those earnings compared to what a worker pays by working.

Ben: To illustrate what Ryan is saying, consider that in 2022—just one year—the wealthiest one-tenth of 1 percent of Americans made $600 billion dollars in capital gains, according to the IRS. By contrast, the bottom half of earners in America in 2022 made $282 billion in wages. So, you know, a population of about 300,000 people, which is literally less than the city of Tulsa where I live, made almost twice in capital gains what the bottom 160 million Americans made from working. That blows my mind.

Glenn: One of the crucial questions you address is this: Does technology reduce inequality or make it worse? Economists like MIT Professor Daron Acemoglu have written about this. What's your answer to that question?

Ben: Some macroeconomic measures that we looked at showed that technology, especially with computers, is making a few people very rich. It's probably driving inequality. It comes back to ownership. If a company like Google can steer all your searches to people that advertise on their platform, then they make the most money from that. Consider Mexico before the 1910 Revolution. The country had high levels of inequality. The problem was that the ownership of technology was all concentrated in a few families in Mexico City. It was great that farmers out in the countryside could get their crops to Mexico City faster on trains, but who made the real money? The owners of the railroad.

Ryan: Today the concentration issue is key. As we've seen with the recent AI boom, the major firms become more concentrated because of increasing returns to scale. The bigger they are, the more able they are to drive out competition and the harder it is to compete. So, they become monopolistic. As they get bigger, they can also keep wages artificially low. Nvidia just reached a $4 trillion valuation. So, yeah, right, I don't see technology as decreasing inequality. It takes regulation—new policy designs—to come in and break it back up and maintain a lower price.

Glenn: One of the central parts of your book is about what inequality does to social cohesion. I think we all agree that we live in very highly polarized times.

Ben: We look at three historical examples and then look at America today. We looked at Romanov, Russia between 1904 and 1918. We looked at Mexico between 1910 and 1920 and Bourbon France in 1789. Let’s just mention France and the French Revolution. Research showed that the top 10 percent made between 47 and 53 percent of gross national income in the late 1780s. In the United States today, the top 10 percent made 52 percent of the gross national income.

Glenn: Your book makes clear that a violent revolution, like the one that occurred in France, is not predetermined to happen. I think your point, though, is that the conditions are there in the US to really cause a lot of polarization.

Ryan: It's not predetermined. Of course. But we also bring up the example of the Irish Potato Famine as an example of what happens when a tiny minority of people control policy and control assets. It has real world impacts that can be literally deadly. Ireland in the 1840s probably could have ended up with a lot of dead Englishmen, but fortunately the Irish were able to emigrate. They could get on a boat and come to the United States. Americans today do not have an option to emigrate. What we still have is the capacity to change the economic policy designs. If we don’t, then we're just going to be widening the gap further. More people will be sick, more impoverished, more desperate.

Glenn: Inequality by Design provides ideas for policymakers and ordinary citizens to improve our situation, to turn the ship, so to speak. However, a lot of people, when they hear discussions about inequality, kind of roll their eyes and say, “Oh, here, come the Marxists.” What would you say to those criticisms?

Ryan: Those arguments have always been there, but remember that inequality is inefficient. It is a sign of market inefficiency. Even if we overlook the ethical issues, inequality has made our economy worse. It makes our stimulus less effective. It makes our markets more volatile. It's not just something that naturally rises out of the market. This is something that results from monopolistic conditions that need to be addressed.

Ben: I think a lot of people believe the free market, almost like an article of faith, always produces the best or the most natural result. But we're not talking about physics here, right? We are talking about human institutions that are designed in ways that either help or hurt people. Right now we have a lot of policies that are designed for inequality. We can change them if we want to.