Pissarro’s Tragic Loss of Creative Work

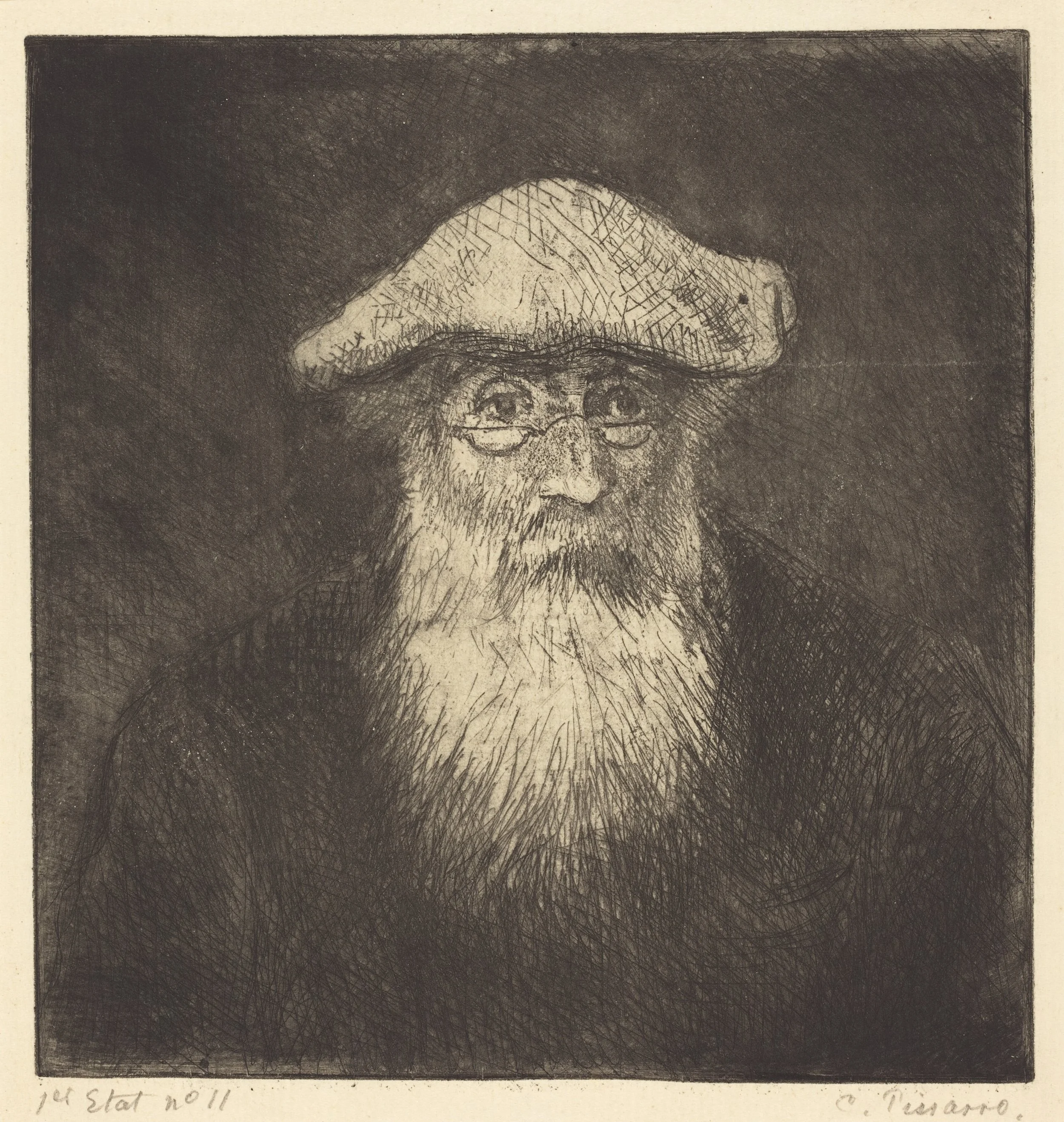

Self-Portrait byCamille Pissarro, circa 1890. Image courtesy of The National Gallery of Art (public domain)

During a recent visit to the Denver Art Museum, I was overwhelmed by the astoundingly beautiful works of Camille Pissarro. With precise, pointillistic brushstrokes, he painted light pouring through gold and green leaves, reflecting off rainy cobblestone alleys, filtering through billowing clouds, and illuminating snowfields.

Then I learned about the tragic disrespect of his creative work. That story, I think, is analogous to what could happen to artists, writers, musicians, and publishers today.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), was a Sephardic Jew raised in the West Indies and in Venezuela. Shortly after Napoleon Bonaparte’s narcissistic empire fell, the Prussian army in September 1870 invaded Paris, where Pissarro had been working for many years. This turn of events dramatically disrupted and reshaped the major art movement known as Impressionism (Paul Johnson, Art: A New History, HarperCollins, 2003).

During the war, which lasted a couple of years, some now-famous Impressionist painters were conscripted to fight for the French. These included Gustave Caillebotte and Auguste Renoir, the latter being drafted into a cavalry regiment. Other prominent painters, such as Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Alfred Sisley were too old to be conscripted, but they remained in Paris while working as volunteers to support the working-class members of the battalions. Collectively, they painted many pictures of the war’s impact on common people (Albert Boime, Art and the French Commune: Imagining Paris after War and Revolution, Princeton University Press, 1995.)

Pissarro, despite being a Danish citizen, wanted to enlist in the French military to defend Paris. As he was about to join the forces, his two-week-old son died. With his wife in shock and despair—making her less able to care for their other young children—Pissarro decided to move his family to London where his sister and mother already lived (Richard Shone, Sisley, Abrams, 1992.)

In the rush to move, he left behind more than fifteen hundred paintings. These works represented the first foray into one of history’s great, new artistic movements—twenty years of one man’s groundbreaking creative work (Denver Art Museum, The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism, exhibition information, December 2025).

While he was in England, the Prussian military took over Pissarro’s home, using the upper floor as barracks. The invading soldiers destroyed all but forty of the paintings. Many were used as floormats. No doubt there were numerous masterpieces in that collection.

Upon hearing about this loss, Pissarro’s friend and renowned painter Claude Monet said, “What shameful conduct … It is frightful and makes me ill. I don’t have a heart for anything. It’s all heartbreaking” (Boime, p. 50).

As for Pissarro’s response, he wrote that the loss of creative work was more painful than the loss of his physical property because the paintings had emanated from his soul and mind. He added that this type of property, what today we would call intellectual property, was “sacred” (Denver Art Museum, exhibition information.)

Thankfully, Pissarro was not a man prone to giving up. He continued to paint until his death, despite a serious problem with his eyes, the loss of another son to tuberculosis, and constant financial struggles. Deciding to explore new artistic expressions rather than remain confined by the popular (and most lucrative) styles of his time, he courageously continued to innovate. For this reason, he is known as the “father of Impressionism.”

“Don’t be afraid in nature: one must be bold, at the risk of having been deceived and making mistakes,” he wrote to his son Lucien (thehistoryofart.org).

As with the other Impressionist painters, Pissarro elevated the dignity of common people and work, including women and children, in a time when most artists painted scenes of wealth and nobility. As the painting below shows, he could “see beautiful things in humble places where other people see nothing” (thehistoryofart.org).

Young Peasant Girls Resting in the Fields near Pontoise, by Camille Pissarro, 1882. Image courtesy of The National Gallery of Art (public domain)

Today’s Threat to Copyright Law

Pissarro rightly viewed the work of humans as being sacred. He believed all work should be valued, protected by law, and honored by society. And yet, today the sacredness of creative work (intellectual property) is being devalued once again. The source of the threat is not war or government; rather, the danger comes from the private sector. Powerful artificial intelligence companies have brazenly stolen trillions of copyrighted books, images, articles, and scientific papers—all to train their algorithms and feed us chatbot regurgitations.

By disregarding copyright laws, the companies are threatening a foundation of our economy. There are now more than one hundred major lawsuits in the US federal court system filed by victims of copyright infringement. The AI companies and others continue to lobby to overturn US copyright laws so that they can have unfettered and free access to the hard work of thousands of scientists, writers, musicians, publishers, and artists. (Ironically, the AI companies have fought hard to protect the copyrights of their own algorithms.)

For those who might not think this issue affects them, consider these facts from the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service.

“A study by the US Patent and Trademark Office found that copyright-intensive industries—such as computer software, motion pictures, music, publishing, and news reporting—contributed $1.29 trillion to US gross domestic product and directly employed 6.6 million people in 2019” (Congressional Research Service, “Copyright Law: An Introduction and Issues for Congress,” March 7, 2023).

What happens if there are no copyright protections for the people who do all that work?

The framers of our Constitution knew that a free society required laws that allow workers to profit from their work. According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the goal of our Constitutional framework is to “encourage diverse forms of expression from diverse creators who [are] fairly compensated for their role in a profitable industry” (Kevin Frazier, “Progress Interrupted: The Constitutional Crisis in Copyright Law,” Harvard Law School, March 13, 2025).

All Americans should push our elected representatives to preserve and strengthen US copyright laws so as to protect the dignity of creators and their work. If the AI companies succeed in abolishing or diminishing copyright protections, then scientists, inventors, artists, writers, and others will lose the motivation and/or the financial capacity to do their work. The downstream economic impact of those losses could be unfathomable. The outcome would be no different than what the Prussian soldiers did to Pissarro’s paintings.

Quote to Consider

“All arts are anarchist when they are beautiful and good.” — Camille Pissarro (Denver Art Museum, exhibition information)